Hiroshima Mon Amour, directed by Alain Resnais, opens with a close-up of an arm and body amorously entangled. They are in the dark, their bodies are joined and small particles, resembling ashes or sand (as the sands of time), are falling and covering them. They are caressing and soon begin to glow, as they are coated in gold or bronze. Due to scarce lighting, their skins are of dark texture, while the one, that of a man, is darker. Soon, we learn they are a Japanese man and a French woman. The first words spoken (by the Japanese man) are “You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing.” She answers: “I saw everything“. Their experiences of Hiroshima are of substantially different quality, she saw the photographic footages and films, in other words reproductions of the event, while he as the member of the Japanese nation felt it to the core. She says that she saw the hospital in Hiroshima; the Japanese man answers: “You didn’t see the hospital in Hiroshima“. The hospital halls are shown in a tracking shot and are presented in a clear, sterile manner with an almost terrifying depth. The shot is juxtaposed to the couple caressing.

She says that she saw the musuem, which portrayed the horrors of the bombing so vividly that the people weeped. She says that she saw the film, capturing the terror imposed on the victims. The horrid scenes of children and women disfigured and mutilated are juxtaposed to the shots of caressing couple. The main theme of the film is introduced for the first time, the one of remembering and forgetting, of the memory that cannot be relinquished. She says: “Like you I am endowed with memory. I know what it is to forget.” He replies: “No, you are not endowed with memory.” As they are entangled in an embrace she connects herself with him regarding the experience of being permeated with memories. Due to unawareness of her life experiences during the Second World War he replies that their positions are not equivalent; the people of Hiroshima were annihilated and those that survived are left disfigured. As the film progresses both the Japanese man and ourselves become aware of the possibility of identification between the Frenchwoman and the Japanese man. She answers: “Like you, I have struggled with all my might not to forget. Like you, I forgot. Like you, I longed for a memory beyond consolation, a memory of shadows and stone.”

The Japanese man, an arhitect, whose parents were killed during the bombing, starts to inquire about Frenchwoman’s past; she gradually exposes herself and her love toward a German soldier in her hometown Nevers during the War. She claims that she had gone mad then, since the German soldier was shot by the French. She was screaming his name, “like a deaf man”, and was imprisoned in the cellar by her family. They cut her hair, depraving her of her femininity. She scratched the stone walls to the point her hands were bloody. She experienced a severe trauma. During the scene in which the Frenchwoman talks about her experiences in Nevers they are sitting in a cafe and the artificial light illuminates her face, while the rest of the film is set mostly in the dark and the light is scarce. She speaks to the Japanese man as he is the German soldier saying: “The only memory I have left is your name.” The Japanese man says to her: “In a few years, when I have forgotten you and other adventures like this one… I’ll remember you as the symbol of love’s forgetfulness. I’ll think of this story as the horror of forgetting.” In other words, although remembering traumatic events can be horrifying, the equal horror lies in forgetting, people and experiences we cherish.

Hi-ro-shi-ma. Hiroshima. Thats’ your name.

The Frenchwoman

And your name is Nevers. Nevers in France.

The Japanese man

In the closing lines of the film, the Frenchwoman calls the Japanese man Hiroshima, and he calls her Nevers. Thus they connect each other with the symbols of trauma and destruction. Earlier the Frenchwoman thinks: “This city was tailor-made for love. You fit my body like a glove. Who are you? You are destroying me. I was hungry. Hungry for infidelity, for adultery, for lies and for death. I always have been.” During this voice-over of Frenchwoman’s thoughts the decaying trees resembling nuclear blast are shown. They bring each other destruction, but the most horrific and the most destructive element of their relationship is that they are aware they will forget each other’s thoughts, feelings they felt for each other and ultimately the time they spent together in Hiroshima. The annihilation (Hiroshima) is not brought by love, but in the instance of forgetting that very love.

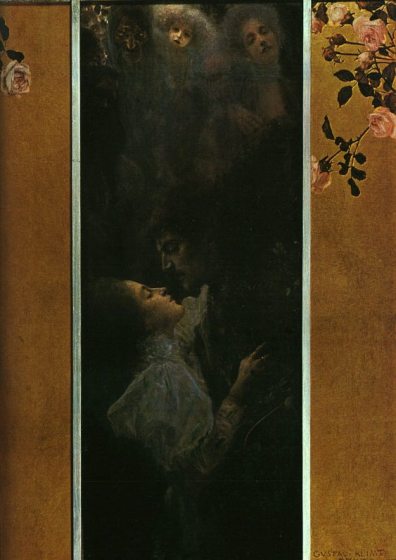

Gustav Klimt, Love, 1895

The painting was found on https://www.gustav-klimt.com/

Note: In this Gustav Klimt’s painting a couple is shown in an embrace, as they are actors on te stage. The man’s face is of darker textures than woman’s, as in a shade, like the ones in Hiroshima Mon Amour. Above them are symbols of death, youth and old age. In Klimt’s painting the juxtaposition between love and death is particularly emphasized, as in the film. Youth is contrasted with old age, and that can be connected to the immediate experiences of youth which we want preserve in memory, but in older age are necessarily forgotten. The young Frenchwoman from Nevers is closely tied with death since her lover died (as in the painting) and as she grows older the painful but inconspicuous process of forgetting ensues.

There is another aspect, which is somewhat hidden under the many layers presented in the film and that is cultural trauma. In his book From Caligari to Hitler, A Psychological History of German Film Sigfried Kracauer writes that “the films of a nation reflect its mentality.” He writes that “what films reflect are not so much explicit credos as psychological dispositions – those deep layers of collective mentality which extend more or less below the dimenson of consciousness.” In other words, films are expressions of collective mentality of a nation at a certain historical moment. Hiroshima Mon Amour was made in 1959, a short time after the French and the Japanese people experienced severe cultural traumas.

For the French it was the defeat by the Nazis and the occupation, but also the collaboration of a part of the French with the Nazis (Vichy France). This can be seen in the film when Casablanca is shown playing in the theater – the film about French resistence – and in the simple fact that the Frenchwoman was in love with a German and her father was forced to close his shop due to her involvement with him. For the Japanese the trauma was defeat in the war and the occupation, as well as the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Frenchwoman and the Japanese man have much in common since both their nations suffered a traumatic defeat and occupation; while for the Frenchwoman the trauma is of personal nature, it reflects the broader context of cultural trauma; the same applies to the Japanese man. The film explores personal and cultural trauma but its main message is the opening of a possibility of connection and empathy between nations since practically all of them have suffered severe traumas in history; the same applies for the members of each nation.

References:

Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler, A Psychological History of German Film, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 2004

One response to “Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959) “…Nevers Mon Amour””

Though I have long admired this film, I find Resnais’s equation of Nazi occupation (after minimal resistance by the French armed forces) with Japan surrendering after two atomic bombs dubious… and “horizontal collaboration” a complex matter (as Resnais showed herein).

LikeLiked by 1 person