The first European Christian missionaries landing in Japan… found their hosts totally unprepared for the message of salvation they brought. Not indifferent however. On the contrary, their preaching… though it was radically at odds with native beliefs, it was warmly received… Baptismal waters flowed. Japan might have gone Christian.

But it was not to be. The nation newly and fragilely unified, a wary regime saw in the sect a vanguard of foreign imperialism. The last straw was the Shimabara rebellion of 1683, an uprising of starving, tax-squeezed Kyushu peasants marching under a Christian banner. It was a glorious, hideous martyrdom –a blood-soaked end to the Christian century.

The Japan Times

Scorsese’s film is based on a historical novel by Shūshaku Endō, a story of Jesuit missionaries who endure presecution in the time of Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”), that followed the aforementioned defeat at Shimabara. The story is presented from the Christian viewpoint, it presentes the struggles of Christians who expect glorious martyrdom, but find cruelty and seemingly meaningless suffering. The presentation of the Japanese side is elaborate enough, so we are confronted with two radically different viewpoints on the nature of truth, the role of state, and the spread of Gospel, on the one side, and the protection against foreign powers and one’s own identity on the other.

At the beginning of the film, Father Ferreira, one of the Portuguese missionaries in Japan, recounts the sufferings of Japanese by the hot springs at Unzen, called “hells” by the Japanese, in mockery of Christian religion. The hot water was poured on Christians, and Ferreira recounts that it was like burning coal. The important notion which should be emphasized at the beginning of this article is the liberal understanding of the role of violence contrasted to tolerance. John Locke argued that violence cannot produce sincere belief, but only hypocrisy and unworthy believers, and is not an adequate answer to the religious struggles within a society. This is, unfortunately, false, as we can see throughout Scorsese’s Silence. Violence can produce the outcome desired by the authority and a doctrine, or its abandonment, can be enforced on its subjects.

Padres Rodrigues and Garupe ask their, superior Father Valignano, to seek out Ferreira in Japan. There are indications that Ferreira apostatized and became Japanese. He was a spiritual Father for the young priests and their need for truth and confirmation (or repudiation) of rumours is strong. Valignano sees it as an act of faith and gives them permission to go to Japan. When they arrive, with the help of a Japanese, who refuses to call himself Christian, yet agrees to help them, they enter a grotto which resembles the belly of a whale. It is black, massive and can be seen as a premonition of the temptations and darkness which they will have to endure.

One of the first observations Padre Rodrigues makes about the Japanese Christians concerns their life in secrecy, their faces are hardened and cannot express Christian love. Nevertheless, he says: I was overwhelmed by the love I felt from these people, even though their faces couldn’t show it. Long years of secrecy have made their faces into masks. During Rodrigues’ voice-over, we can see the Christians surrounded by the immense landscape, the islands, the mountains, the hills are their hiding places amidst the persecution, but this immense landscape also portrays their alienation from it. The fire of faith burns in their hearts, yet, they are strangers in their own land. When Rodrigues stays alone, he sees a raptor and sees it as a sign of God. For him, God is omnipresent, in line with Spinoza’s conviction.

When they come to another Christian village, Rodrigues says: “On that day the faithful received fresh hope, and I was renewed. They came to me” Here, we can see the first narcissistic signs which will be important for the study of Rodrigues’ character and for the crucial moments at the end of the film. We can see the retrospections portraying the deaths of Kichijiro’s family, and his renunciation of faith, which is the reason for his later regrets and shame. Burning on the stake was one of the principal methods of execution in Tokugawa Japan and soon, we will see another form of execution which was typical for the regime, crucifixion. Although it was associated with Christianity in the West, its roots in Japan are not connected to it. Nevertheless, in the film, it will be practiced as a kind of mockery on the part of the Japanese.

The soldiers come to the village, and the Christian villagers say: “We do our duty to the State. We worship Buddha at the temple.” The Tokugawa regime seems to operate like a Hobbesian sovereign, who is the only one who can prescribe the state’s religion, which doctrines are true and which ones are false. For Hobbes, to permit everyone to practice what they want, is a precept for the state of nature, i.e. war. Buddhism, in this case, is the state religion and all deviations result in a deliberate refusal to follow state’s authority and thus the sovereign is openly attacked.

Rodrigues thinks: “I prayed to undergo trials like his son”, and his prayers are soon granted. The villagers refuse to spit on the cross after they nonchalantly step on the image of Virgin Mary, abiding to Rodrigues’ advice, and they are tied to the crosses in the ocean. The waves relentlessly splash on them for days, and the one the villagers with the strongest spirit, Mikichi, endures everything with dignity and passion, singing hymns just before he dies. It is crushing, but impressive scene; the violent forces of nature confront the strength of the spirit. Scorsese himself said that filming this scene was an overwhelming spiritual experience.

Rodrigues watches their martyrdom with amazement; he sees them as a “faceless Other” who is willing to sacrifice for his own beliefs, thus enhanching his sense of purporse and his own mission. He questions God’s acknowledgment of their suffering, and perhaps, his own: Surely God heard their prayers as they died. But did he hear their screams? Rodrigues does nothing to prevent the crucifixitions. As a Jesuit priest, he is far more valuable to the Japanese than simple peasants.

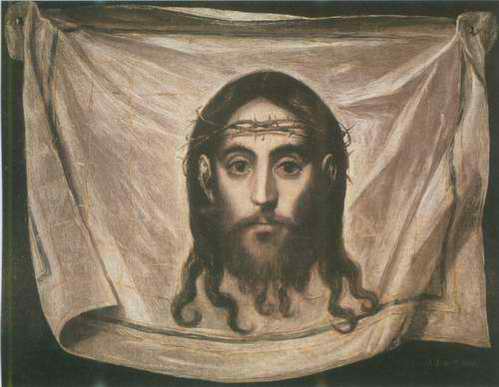

Rodrigues ruminates on the weight of God’s silence and in a long shot he is shown small amidst the vast landscape; thus his powerlesness is in contrast to the foreign and hostile soil. He meets Kichijiro again, who tells him that there is a reward for turning a priest in, the amount is 300 silvers. Rodrigues replies that Judas got only 30. Again, he compares himself to Christ’s destiny, emphasizing the irony; Christ was sold for less than he is about to be sold. He looks in the stream he is drinking from and sees his own face, with messy hair and at the same moment he sees El Greco’s Christ in his own image. He starts to laugh frantically; Narcissus looked at the lake and fell in love with his own image, and drowned. Rodrigues’ image and the image of Christ coalesce and his narcissism is thus portrayed as being on the verge of sanity. It is indicative that at the same moment he is captured by the Japanese, due to Kichijiro’s betrayal.

Kichijiro is both a pitiful and comic character, he is some kind of a miserable and abject Sancho Panza, while the missionaries’ attempt to transform Japan into a Christian country is akin to advantures of Don Quijote in many aspects. It is a tale of foolish bravery and dedication, abundant in dangers, victories and defeats, but also a tale of illusory conquest. Kichijiro’s persistent cries for confession and absolution are comical, and just as Nietzsche says that we, the moderns might find it difficult to laugh at Cervantes’ work, while the people of renassiance laughed sincerely, the same can be said about Scorsese’s Silence, at least about some of its aspects. Executions are no laughing matters, but seeing Kichijiro persistently crying for absolution might as well be comical. Japanese peasant woman happily saying that paraiso must be better than life on Earth (i.e. it is better to die), since there are no taxes in heaven and no hard work, looks like a line written by Stendhal and not a Japanese Christian novelist.

When Rodrigues meets inquisitor Inoue for the first time, a representative of Hobbesian sovereign power, Inoue tells him: “The price for your glory is their suffering.” We can see the outlines of Inoue’s understanding that missionaries’ attempt to bring Christianity to Japan is an imperialistic conquest which brings glory to the missionaries themselves while the people suffer unnecesseraly. In other words, they are an intrusion, which brings pointless sacrifices, heroic they are, but the Tokugawa regime is determined not to succumb. Martin Scorsese said in an interview, that if the missionaries succeded, there would be no more Japan. His admiration for missionaries is evident, especially at the end of the film where it is written: For the Japanese Christians and their pastors: Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam, yet, Scorsese seems to acknowledge that the missionaries’ attempt was an act of cultural imperialism.

This brings us to the discussion between Inoue and Rodrigues. The interpreter says: But everyone knows a tree which flourishes in one kind of earth may decay and die in another. It is the same with the tree of Christianity. The leaves decay here. The buds die. He accuses Rodrigues of arrogance, he says that he respects his religion, but that Rodrigues doesn’t respect their own. Padre’s conviction is that truth is universal, if the ideas of Christianity are valid in Portugal, they must be in Japan as well. The intrepreter says that the Japanese have studied Christianity carefully, that they find it dangerous and of no use in Japan. Scorsese provides a well-balanced discussion, both sides have their own epistemology (for the Japanese it is cultural relativism) and elaborated arguments. The arguments of John Gray, a political philosopher of post-liberalism, are similar to the arguments of the Japanese. There is no universal order of things which should be applied everywhere in the world, following Hobbesian doctrine he advocates peaceful coexistence of different religious and political orders and value pluralism.

The discussion between Inoue and Rodrigues is particularly interesting because it shows the impossibility of meaningful mutual understanding. Inoue speaks of four concubines which plague daimyo’s mansion and by expelling them, he brings himself peace. For Japan, these concubines are Spain, Portugal, Netherlands and England. Rodrigues speaks of taking one lawful wife, the Church. Inoue’s understanding is geopolitical, he sees Christianity as a form of exterting influence with imperialistic pretensions. Rodrigues only sees the act of spreading Gospel, truth and love.

When Rodrigues finally sees Father Ferreira, who is now Sawano Chūan, both are overwhelmed. When Ferreira approaches, natural light illuminates the palace and we see a scene which is far more visually structured than the rest of the film. Immense landscapes are replaced with serenity of a palace, yet, the grief is apparent on Ferreira’s eyes. He tells Rodrigues that It is fullfilling to finally be of use in this country. Now, he writes about astronomy and medicine, disciplines which need to be developed in Japan, but acknowledges that there is much wisdom in Japan. They debate on the possibility of implanting Christianity in Japan. The interpreter says: No one should interfere with another man’s spirit.

These words are illuminating for the narration, but both sides seem to be involved in the endeavour. Ferreira’s soul has been twisted and tortured in a cruel manner, as we can see from the flashbacks and as Rodrigues puts it, yet from the Japanese perspective, this attempt of the transformation of the souls was the missionaries’ attempt from the start. Ferreira says: The Japanese believe only in their distortion of our gospel. So they did not believe at all. They never believed… Francis Xavier came here to teach the Japanese about the Son of God. But first he had to ask how to refer to God. “Dainichi” he was told. And shall I show you their “Dainichi”? Behold. There is the Son of God. God’s only Begotten Son. In the scriptures Jesus rose on the third day. In Japan, the Son of God rises every day. The Japanese cannot think of an existence beyond the realm of nature. For them, nothing transcends a human. They can’t conceive of our idea of the Christian God.

Toward the end, Rodrigues is confronted with a choice. He can either let Christians suffer in the pits and leave them dying for days, or he can apostatize and save them. Ferreira appeals to his judgment by saying that he is prideful and is comparing himself to the trials of Christ. He asks him, what would Christ do? Would he let people suffer or abide. Ferreira says to him: You are now going to fulfill the most painful act of love that has ever been performed. Rodrigues hears God’s words, “It’s all right. Step on me” and steps on the image of Christ. The question is, why does he do it? For Christians, the suffering of the body and physical death is only a path to salvation. Was it only compassion that drove him to renounce his faith, his identity, very heart and soul?

The answer may be, that he acknowledged his defeat, and the defeat of the Jesuit endeavour to Christianize Japan. With this act, he renounced his faith in public, but stayed a Christian nevertheless. This was an act of acknowledgment that, regarding their mission, all is lost. Inoue’s words are a final verdict: the roots have been cut. Rodrigues takes the Japanese name and a wife, and lives in Japan for the rest of his days. In the final scene, after his death, which ocurred naturally, we see him holding a cross. He internalized his faith, he was unable to practice it, but that was the consequence of his decision. And he lived bravely with those consequences.

Thanks for reading!

You can also read the article about this same film,“The Dark Night of the Soul”, from the Christian perspective, chronicling the struggles of Jesuit missionaries, mainly Sebastiao Rodrigues.

13 responses to “Silence (Martin Scorsese, 2016) “Last Breaths of Christendom In the Land of the Rising Son””

I’ve never seen this film, but it certainly seems like a fascinating period piece – one centered on a part of history that doesn’t get too much attention. I do like Martin Scorsese, so I may have to check this one out in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You definitely should, it is fascinating. I watched it three times and it only gets better with repeated viewings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great essay. It is a brilliant film and it does get better with repeated viewings. It is really fascinating to follow Rodrigues as a character and his transformation. I remember in my review, I particularly focused on the themes of faith put in context and the nature of evil. I think an underlying message is also one’s belief not necessarily being reflected in outward action. Who is to know how a person really feels or what he continues to believe in, or what form his private relationship with God takes? Faith is also a completely internal and private matter, and therefore in the end it is difficult to judge how strong or correct one’s faith is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I truly appreciate it! Interpretation of the film which focuses on the nature of evil and faith can be an interesting one, since the film abundantly deals with those subjects. The schism between the belief and action is also evident and I believe that it can be an interesting matter to discuss as well, As a political scientist, I focused on the so-called “Hobbesian moment” and the nature of the role of state in relation to the practiced beliefs. For example, Gray also argues that some authoritarian governments like Singapore, have an interesting model of the state-religion relation. You can practice anything you want, but you cannnot apostatize. I wanted to focus on such arguments, since I believe that the interpretations of Silence do not give enough attention to these themes. I agree that it is difficult to argue if someone “internalized” faith or not; my argument falls in line with the opposition between public practice (preaching, baptizing etc.) and an internal communion with God (if it exists, and when Rodrigues is considered, the ending is rather straight-forward, as far as I interpret it).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, you put it very well in your essay about the apostasy. But, I am still not overly convinced about Rodrigues apostatising because he knew everything is already lost. That may have been part of the reason, but the reasoning here is also a bit more complex, I should think. I know the importance of the action, the gravest sin for the priest, the second death, etc. and the Japanese reached their goal with Rodrigues. However, regarding Rodriques and his personal faith and relation with God, there is also that distinction between morality and faith. Saving a number of people’s lives is an action of love, sacrifice well beyond anything, and he also realised that. He put Christians first and the argument could be that it was not on his own volition that he apostatized – a forced action of that kind is also not a true action, and there have been cases of priests being forgiven by “God” for their action. In relation to his personal faith, there could be all that reasoning in his mind and many many others. I know all these are not “defences” to his public faith renunciation, but still, his action and psychology behind it are far more complicated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, you nailed it! Of course, “all is lost reasoning” is only a part of his motive. It is much more complex from a religious point of view. I mentioned Locke’s idea that forceful apostasy means nothing, and it might as well be truth. Yet, from the state’s point of view – mission accomplished.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have given me much to consider – I truly appreciate your careful analysis. I know little about movies in general, but you show unequivocally that film is an intriguing and complex art form. “Silence” is added to my growing list. Great post! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your kind words. 🙂 I appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Silence (Martin Scorsese, 2016) – I have seen a fair share of Martin Scorsese films, but Silence is not one of them. Vigour of Film Lines wrote an interesting article about it, and I have to say I’m interested in checking it out because the subject matter is quite fascinating. […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

I found the film’s backstory and Martin Scorsese’s personal/spiritual relationship to the source material more interesting than the film itself. Your interpretation of the cultural relationship between the evangelistic Europeans and protectionist Japanese is illuminating. Questions raised with regards to not just spiritual coexistence, but moral relativism vs. absolutism (e.g. if other cultures restrict the rights of their citizens, do we have a moral obligation to criticize that?) are fascinating.

As a film, however, I found Silence to be my least favorite Scorsese film. I haven’t watched his entire filmography, but this is the only film of his I dislike and never intend to rewatch. I found his sheer lack of visual style disappointing, the long running-time poorly paced, and the repetitive portrayal of torture repetitive to the point of numbing. And don’t get me started on that Kichijiro…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, it is a writer’s greatest pleasure if someone finds the ideas interesting and thought-provoking.

After my first viewing of the film, I felt exactly the same as you do. I believe that the lack of visual style was Scorsese’s intention. He wanted to make it bare and truthful as possible. I also thought that the pacing is terrible etc., yet with repeated viewings I started to cherish it more and more. Mostly the ideas presented. Ah, Kichijiro….

LikeLike

[…] this year, I wrote an article about this very film, “Last Breaths of Christendom in the Land of the Rising Son”, emphasizing the role of the Japanese state (Tokugawa Shogunate) and the Hobbesian reading which […]

LikeLike